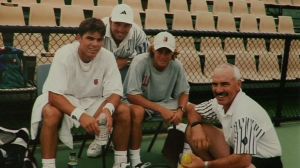

Peter Carter and Roger Federer

CLICK HERE to watch the Virtual Tennis Coach tribute to Peter Carter

In professional tennis, the only crime worse than lacking world-class talent is squandering it. For years, the curse of untapped potential hung around Roger Federer’s neck like an anvil, as the waited with growing impatience for his big breakthrough. With no holes in his game, fans simply assumed the only thing the fluid, efficient Swiss star needed was character. One life-altering tragedy and 13 Grand Slam titles later, all is forgiven and forgotten, as Roger has brought an element of artistry back to the men’s game. This is his story…

GROWING UP

Roger Federer was born August 8, 1981, in Basel, Switzerland. His parents, Robert and Lynette, both worked in the pharmacuetical industry. Robert was an executive for Ciba-Geigy. He met Lynette, a native South African and also a Ciba-Geigy employee, during a business trip. Their marriage also produced a daughter, Diana, in 1979.

Roger and his older sister grew up in the town of Munchenstein, just outside the city of Basel. A 2,000-year-old city on the Rhine, it is home to Switzerland’s oldest university, dozens of museums and the famous Theater Basel.

Tennis was a family passion in the Federer home, though neither Roger’s parents nor his sister had any special aptitude for the game. Everyone enjoyed it, however, and Roger showed enough promise to earn entry into Basel’s crack junior program at the age of eight.

Roger’s first sports hero was Boris Becker, the young German who won Wimbledon in 1985. Roger recalls watching Becker play Stefan Edberg in the 1988 Wimbledon final. He cried when his idol lost. Controlling his temper was a problem that would plague Roger throughout his childhood.

His game already showed signs of genius, but like many kids his age, he was often out of control on the court. (Roger describes himself as a “hothead.”) He erupted after hitting dumb shots and rarely went through a day without hurling his racket against the fence. Robert and Lynette were mortified when they saw their son’s behavior during tournaments. Roger could not understand this. He was never rude to umpires, linesmen or opposing players. His anger was reserved for himself. The Federers refused to speak to him after one of his episodes, frustrating him even more.

Enter Peter Carter. A tough player from Australia, he had learned how to make a little talent go a long way. From the age of 10 to 14, Roger spent more time with Carter than his own parents. The coach taught Roger flawless technique on his ground strokes and serve, and watched him grow into his body and start dominating opponents. The two also discussed the mental side of the game—not just strategy and psychology, but also about the importance of being gracious and polite and reigning in your emotions. Carter was eventually able to get Roger to see how much energy he wasted during his outbursts, and over the next few years, the incidents lessened considerably.

In 1994, at the age of 13, Roger decided it was time to leave home and accept an invitation to Switzerland’s national training center in Ecublens, near Lausanne. He would come home on weekends and spend time with his family, but every Sunday night, when it was time to board the train for the two-hour ride back, he was terribly depressed. The training center was in the French-speaking part of the country. Roger, who spoke German, found himself isolated by many of the students and coaches.

Three years later, he left Ecublens and re-enrolled in a new training facility in Biel, where Carter had been put on staff. Reunited with his coach, Roger began a steady rise to the world’s top junior ranking.

In 1997, Peter Lundgren, a former ranked ATP player from Sweden who had once coached Marcelo Rios, joined the staff and worked with Roger on occasion. He helped to refine Roger’s already-silky strokes and hammered home the self-control message on which Carter had made such good headway.

The following year, Roger distinguished himself as the mot polished teenager in tennis and earned the ITF’s #1 world ranking, capturing the Wimbledon junior singles (versus Irakli Labadze) and doubles titles, as well as the Orange Bowl (versus Guillermo Coria) in Florida. He also reached the finals of the junior draw at the U.S. Open, but lost to David Nalbandian.

Only Edberg, Pat Cash and Bjorn Borg had taken the junior singles at Wimbledon and then gone on to win the senior singles. Aiming to be the fourth, Roger decided it was time to join the men’s tennis tour. After signing a representation deal with IMG, he played some year-end mop-up events and did well enough, reaching the quarterfinals in Toulouse—just his second ATP tournament—and winning the singles and doubles in a Swiss satellite event to finish the season.

Instead of tabbing Carter as his coach for his first full pro season, Roger chose Lundgren instead. Once a Top-25 player, Lundgren had insights into the pros that Carter did not. Roger still consulted frequently with his former coach, and within a couple of years, he engineered the ouster of Swiss Davis Cup captain of Jakob Hlasek so that Carter could step into this role. As Switzerland’s best young player, Roger had the power to do this.

Roger played well in 1999. He reached the semifinals of a tournament in Vienna and advanced to the quarters in Marseille, Rotterdam and Basel. His biggest victory came over Carlos Moya, who was ranked #5 at the time. Roger also won a Challenger-level event in Brest, defeating Max Mirnyi. By the end of the year, he was the youngest member of the ATP Tour’s Top 100.

Peter Carter

CLICK HERE to watch the Virtual Tennis Coach tribute to Peter Carter

ON THE RISE

The 2000 season brought Roger his first two ATP finals appearances. He lost to countryman Marc Rosset in Marseille in a final-set tiebreak and to Tomas Enqvist in the finals at Basel. Roger was playing about .500 tennis until the U.S, Open, then finished 16-9 through the end of the year.

By far the highlight of Roger’s ’00 season was representing Switzerland at the Olympics in Sydney. He lost his quarterfinal match, barely missing out on a medal, By then Rogerhad become smitten with a member of the Swiss women’s team, Miroslava Vavrinec. Their relationship blossomed in the ensuing years, and she eventually was considered a member of the Federer family.

Roger finally got on the board in 2001, winning his first ATP singles title in Milan. He defeated Goran Ivanisevic, Evgeny Kafelnikov and Julien Boutter on his road to the championship. From there, Roger led the Swiss Davis Cup team to victory over the United States by taking both his singles ties as well as the doubles. The first “Federer Express” headlines began appearing soon after.

The best was yet to come. With everyone handing the Wimbledon crown to red-hot Pete Sampras that year, Roger stepped up and beat the American star in five sets to end his 31-match winning streak. Tennis fans thought this might be Roger’s long-awaited breakthrough, but he lost in the next round to Tim Henman. It was not the first time he had followed a significant win with a perplexing loss, and it would not be the last.

Roger spent the rest of the summer nursing a groin injury. He reappeared at the U.S. Open—where he lost to Andre Agassi in the fourth round. Roger picked up his game when the European indoor tournaments rolled around, reaching the final in his hometown of Basel after an impressive win over Andy Roddick. Henman was waiting for him in the final, however, and beat him for a second time that year.

Roger claimed his first two ATP doubles titles in ’01, in Rotterdam with Jonas Bjorkman and in Gstaad with Marat Safin. He ended the year ranked #13 in singles and got high marks on all surfaces. He had a winning record on hardcourts, grass, clay and carpet—an unusual feat for a developing player. Roger barely missed securing one of the six slots in the season-ending Masters Cup. He made it his goal to reach that tournament in 2002.

Roger started the ’02 season with a victory at Sydney, an important tuneup for the Australian Open. He began the Open well, advancing to the round of 16 without trouble. Then he ran into Tommy Hass. Though he was handling Haas—Roger actually had match point—the pesky German fought back and won in five sets, taking the decider 8-6.

Waiting for Roger to claim his place in the Top 10 was becoming a frustrating process for his fans. After every signature vicotry, there seemed to be a deflating loss. This is not unusual on the men’s tour, but in Roger’s case, he won with such creativity and style it was hard to see how he was ever defeated. In Key Biscayne, he upended #1 ranked Lleyton Hewitt and seemed unstoppable on his way to the final, where Andre Agassi cleaned his clock.

From a player’s perspective, you were never sure which Federer was going to show up. And you didn’t always find out right away. For every guy Roger blew off the court, there was someone else who hung in until he lost his rhythm, and suddenly it was a match again. At the ’02 French Open, Roger was beaten by Moroccan journeyman Hicham Arazi in the first round. A week earlier, at a clay court tournament in Hamburg, he had destroyed Gustavo Kuerten and Marat Safin to win his first Masters series event.

As the summer tournaments rolled around, Roger managed to creep into the Top 10 for the first time. But he was still vulnerable in long matches. It wasn’t a matter of conditioning, but rather one of mental toughness. Roger knew it, too. After four- and five-set losses, he would weep out of frustration in the locker room. When he lost in the first round at Wimbledon in straight sets to 154th-ranked Mario Ancic, some of his most ardent fans began siding with his detractors; perhaps Roger did not have what it took after all.

Despite Roger’s claims to the contrary, the pressure of his as-yet-unfulfilled potential was starting to get to him. He had always been despondent after bad losses, but it was getting harder and harder to shake them off. To get to sleep, he would bang his head into the pillow repeatedly to release the tension.

Roger dropped another first-rounder that season at an August tournament in Toronto. He stuck around to compete in doubles, but was basically just partying at night instead of preparing for his matches. One evening, Roger went out for beers with some other players after attending a Cirque du Soleil performance, and ignored Lundgren’s repeated attempts to summon him on his cell phone. Finally, his coach called Wayne Ferreira and got through to Roger. Peter Carter was dead, Lundgren told Roger. Talk about guilt—it was at Roger’s urging that Carter had gone on safari in South Africa. His vehicle had veered off the road and fallen into a ravine. He and the driver were killed instantly.

Roger lost it. He bolted into the street. When he couldn’t find a cab, he panicked and just started running. He ran more than a mile until he gained his bearings and made his way back to the hotel. Roger returned to Switzerland to see to the arrangements for Carter’s funeral. The body arrived in Basel on his 21st birthday.

Carter’s death forced Roger to focus on his life, his game and his relationships. As a young pro, he had brushed aside some of what Carter had taught him about being a good player and a good man. Now he wanted to honor his old friend by finally embracing these qualities.

It didn’t happen overnight. Roger played the U.S. Hardcourts in Cincinnati and was beaten soundly in the first round, and then won only three matches in Flushing Meadows before bowing out of the U.S. Open. Roger finally began to turn things around later in September, when he avenged his loss to Harazi in a Davis Cup tie against Morocco. Roger teamed with George Bastl to win the doubles andbeat Younes El-Aynaoui to wrap up the series. In each match—they both ended 6-3, 6-2, 6-1— it was like watching a tennis God toy with mere mortals. Someone had flicked on the switch.

Roger finished the year strong enough to earn a #6 ranking, and was the only Top 10 player to win multiple singles and doubles championships—teaming with Mirnyi for titles in Rotterdam and Moscow.

Roger easily made the season-ending Masters Cup draw. He won the round-robin phase of the tournament andmet Hewitt in the semis. The two young stars pounded away at each other, splitting the first two sets 7-5 and 5-7. Roger was outlasted by Hewitt 7-5 in a classic third and final set, but he impressed tennis experts with his newfound grit against a superior player.

Never afraid to move forward—or move on—Roger decided to end his long relationship with IMG in 2003 and asked his parents to handle the bulk of his business dealings, adding an attorney and media consultant to Team Federer.

Roger started the year on fire, winning his first 10 matches and capturing singles titles in Dubai and Marseille. He lost in the fourth round of the Australian Open, but kicked back into high gear that April in Davis Cup play. Roger won both of his singles matches and the doubles to defeat France 3-2.

When the clay court season began, Roger took the first tournament in Munich without dropping a set. He also reached the finals of his next event. But at the French Open, Roger bowed out again in the first round, this time to Luis Horna.

Peter Carter

CLICK HERE to watch the Virtual Tennis Coach tribute to Peter Carter

MAKING HIS MARK

Roger righted himself when the men’s tour moved to grass, winning at Halle, one of the tune-up events for Wimbledon. He was firing on all cyliders at the All-England Club, and for a change things seemed to be breaking his way. Co-favorites Hewitt and Agassi lost early, which meant the spotlight was retrained on Roger and Roddick, who were both unbeaten on grass in ’03 as they headed for their semifinal clash.

It was all Roger could do to get on the court for this match after straining his back during his fourth-round victory over Feliciano Lopez. Deep massage, pain pills, and a shot at his first Grand Slam kept him going.

There was still the small matter of Roddick. The favorite to advance to the final and win it all, he hadn’t lost in more than a month—and had his serve working. The fact that Roger had never gone this deep into a Grand Slam before did not help his cause with the odds-makers, who believed that he was once again in over his head.

A day before the Federer-Roddick match, tennis legends John McEnroe, Boris Becker, Martina Navratilova and Ilie Nastase authored an open letter to the ITF claiming that serve-and-volley tennis was dead, and that new rules needed to be implemented to save the beauty of tennis. Roger answered their charges in eye-opening fashion, demolishing Roddick in straight sets with a masterful display of all-court tennis. Roddick played well and served bullets, but had no answer for the game Roger brought to centre court that day.

In the final, Roger faced the only guy on the tour with a serve harder than Roddick’s, Mark Philippoussis. The Aussie held serve most of the time, but was overmatched by Roger once points went into play. The final score of 7-6, 6-2, 7-6 made the match look closer than it was. At no point was the outcome really in doubt. With the Grand Slam monkey off his back, Roger set his sights on a #1 ranking.

Roger reached the final in his next tournament, in Gstaad, but lost to Jiri Novak, ending his unbeaten streak at 15 matches. At the U.S. Open, he lost in the fourth round to David Nalbandian. So much for #1. After the tournament, Roger sucked it up for what he knew would be an emotional meeting with the Australian Davis Cup team.

The winner of this competition would not only get to the finals, it would claim the first Carter Cup, named in honor of Roger’s old coach. Anytime Switzerland and Australia compete in tennis, the trophy is on the line. Roger won his first match, but by the time he faced Hewitt, the Swiss were down 2-1. He played inspired tennis and took the first two sets. Up 5-3 in the third set, Roger failed to chase after a pretty shot by Hewitt that he assumed was going out. This one point turned the match around, giving Hewitt extra fire in his belly andRoger too much to think about. He lost the third and fourth sets, and then Hewitt ran him off the court in the fifth, 6-1. Roger rushed to the locker room sobbing.

Carter’s parents met with Roger privately after the match and tried to console him. They told him that in Roger’s tennis, they saw their son living on—that when they pulled for Roger, it was like pulling for Peter. This meeting enabled Roger to appreciate Carter’s life lessons on a much deeper level. Some say Roger finally transitioned from boy to man after this meeting in Melbourne.

Prior to the season-ending Masters Cup in Houston, Roger got on the wrong side of tournament chairman “Mattress Mac” McIngvale and endured a tongue-lashing that might have sent him packing in the past. Choosing to stay, he unleashed his anger on Agassi in front of a rabidly pro-Agassi crowd. Roger also destroyed Nalbandian and the new world #1 Roddick on his way to the final, where he beat Agassi again. It was a nice way to end the season.

Despite having just completed the finest year of his career, Roger fired his coach, Lundgren. Their relationship, he felt, had become too cozy. Roger needed someone who could rattle his cage when necessary. He believed he and Lundgren had been through too much together for that to happen.

Roger started the 2004 campaign with his second Grand Slam title, at the Australian Open. He was on top of his game, as he cruised through the draw and defeated Safin in the final. The victory convinced any remaining disbelievers that Roger had arrived, and vaulted him to the tour’s #1 ranking for the first time.

Roger held that ranking with tournament wins in Dubai, Indian Wells and Hamburg. The victory on clay in Germany was a significant one. Unlike the players to whom he was now increasingly being compared—Sampras and McEnroe—Roger was a killer on clay.

For this reason, he was installed as the favorite at Roland Garros. But a tough loss to Gustavo Kuerten in the third round derailed his dream of winning four Grand Slams. After the French Open, however, the Federer Express just kept rolling.

Roger took his next four tournaments, including Wimbledon. He outplayed Roddick and out-strategized his coach, Brad Gilbert, during a rain-interrupted final. The two young stars sparred for two-plus sets and sat through two delays before Roger finally found his rhythm and began playing his A Game. Even so, Roddick gained several break points in the third and fourth sets, but Roger did a great job fighting them off. He won 4-6, 7-5, 7-6 (7-3), 6-4. After the match, all Roddick could do was shake his head in admiration. He had thrown everything he had at Roger, to no avail.

At Wimbledon, Roger showed the tennis world two things it had been waiting to see: he could win against a Top 10 player when he wasn’t at his best, and he could adjust to changing strategies and conditions. It was a truly artistic victory against an overpowering player and a coach who delighted in “winning ugly.”

Prior to the U.S. Open, Roger joined the Swiss team in Athens for the Olympics. He lost in the second round to Tomas Berdych, but had a good time at the games. The defeat turned out to be the last one of the year for Roger. Incredibly, he ran the table the rest of the way.

Roger’s sternest test came in the quarterfinals at Flushing Meadows against Agassi, as wind, rain and a vociferous home crowd threatened to throw him off. Yet just as he had at Wimbledon, Roger adjusted again and won. The semifinals brought a familiar nemesis in Henman, but this time it was barely a match, as Roger blew him off the court.

In the final against Hewitt, Roger authored a near-perfect opening set. Stunning Hewitt and the crowd, he won 6-0 in under 20 minutes. Roger went up 5-2 in the second set but stumbled and let Hewitt back in the match. He recovered to take the tiebreak, and then blanked Hewitt in the third, 6-0. Those who knew both men were shocked. Hewitt’s greatest asset, his tenacity, had all but disappeared by the final set. Roger’s longtime flaw, his lack of grit, was all but absent during the match.

Tennis fans were gushing about the tour’s first three-Slam champ since Mats Wilander in 1988. Roger was not only hailed as the leader of the game’s new wave of male players, he was saluted for his “throwback” style.

Roger ended the season at the Masters in Houston, winning the tournament without a hiccup. This was Hewitt’s chance to reassert his former dominance over Roger. Instead, Roger clobbered him in their round-robin match. He beat Hewitt again in the finals, in straight sets—the sixth victory against the Aussie in ’04 against no losses.

Roger finished the season with only six losses and was a perfect 11-0 when he reached the finals of a tournament. In his final 23 matches against Top 10 players, he was perfect, too, going 23-0. It had been more than 30 years since a player had dominated the men’s tour to this degree.

A few days after the conclusion of the ’04 season, Roger began thinking about 2005. He was determined to improve his stamina and mapped out a more rigorous regimen and diet plan.

Roger’s first test of the ’05 season came at the Australian Open. He breezed through the early rounds, including a decisive victory over Agassi. In the semis, he met Safin, who had his eye on the #1 ranking. The match was a classic, as the two slugged it out for nearly five hours. They split the first four sets, delighting the SRO crowd with their all-out effort on every point. Several times Roger showed the strain of keeping his 26-match unbeaten string intact as he screamed at himself in anger.

Heading into the fifth set, he needed treatment on his right shoulder and elbow for pain that he later called more of a nuisance than anything else. Safin kept the pressure on, making Roger chase down balls all over the court. Trailing 8-7, Roger served to stay alive. With a chance for a break to win the match, Safin drove a shot deep to Roger’s forehand. He lunged in desperation, but dropped his racket as he hit his return. With Roger totally defenseless, Safin ended the thrilling match with a simple putaway. The final line score read 5-7, 6-4, 5-7, 7-6 (6), 9-7.

Roger rebounded to win the big ATP Masters events in Indian Wells and Miami. In the latter, he fought back from two sets down in a spine-tingling final to win in five sets. His victim was an 18-year-old Spaniard named Rafael Nadal. The two had met in Miami a year before, and Nadal had cleaned Roger’s clock. As the two warriors left the court after their epic final in 2005, their mutual respect was obvious. A rivalry was beginning to bloom. Their next meeting came at the French Open. Clay was Nadal’s best surface, and he beat Roger in a four-set semifinal on his way to his first Grand Slam singles victory.

At Wimbledon, Roger went through the draw like a buzzsaw, disposing of Fernando Ganzalez and Lleyton Hewitt in the quarters and semis. In the final against Roddick, Roger dominated the opening set, won the second in a tiebreaker, and closed the American out in the third 6–4.

Roger was untouchable at the U.S. Open. He did not lose a single set on his way to the semifinal against Hewitt, whom he beat in four sets. Roger bested Agassi in the final 6–3, 2–6, 7–6, 6–1. He finished the year at #1 again. There were really no weaknesses in his game at this point. Some were saying that he deserved to be mentioned among the greatest players of all time.

Nothing in 2006 diminished this observation. Roger practically slept through the Australian Open, beating Nikolay Davydenko, Flag of Germany Nicolas Kiefer and Marcos Baghdatis in the final three rounds. He got his wakeup call when the clay court season began, as Nadal beat him in Monte Carlo and Rome. The match in Italy lasted five hours, and Roger saved two match points in the fifth-set tiebreaker. It added yet another chapter to what had quickly become the most compelling rivalry in tennis. When Nadal beat Roger in the French Open final, their story was one of the most talked-about in sports.

Roger won Wimbledon again, taking every match in straight sets on his way to a final showdown with Nadal. Roger wiped him out 6–0 in the first set, captured the second-set tiebreaker and then finished him off in the fourth set. Nadal may have been the master of clay, but on grass Roger was still the man.

And on hard surfaces, too. Roger claimed the U.S. Open for the third year in a row, surviving a tough quarterfinal with James Blake and defeating Roddick again in the final. At the end of the year, he beat Blake in the finals of the Masters Cup, winning it for the third time in four seasons. Roger was number one again. Behind him at #2 was Nadal, but he was just a speck in the rearview, thousands of points behind. That would start to change in 2007.

Roger began the year by winning his 10th Grand Slam singles title at the Australian Open. Once again he cruised through a lackluster field, dispatching Fernando González in the final. Roger took the championship without the loss of a set. He ran his consecutive match streak to 41 before losing at Indian Wells to Guillermo Cañas. He fell to Cañas again at the Sony Ericsson Open in Miami, leading some to speculate that either: a) Cañas knew something no one else did, or b) that something was wrong with Roger.

Roger lost to Nadal in the finals at Monte Carlo and dropped a match to another journeyman in Rome. That made four tournaments in a row without a trophy. However, just when people were whispering he was vulnerable on clay, Roger beat Nadal in the final at the Hamburg Masters. It was the first time he had defeated the Spaniard on the slow stuff. Nadal bounced right back at Roland Garros, denying Roger the French Open for a third consecutive year.

Heading into Wimbledon, Roger was well-rested. He skipped the warm-up tournament in Halle, which he had won each year since 2003, and tore through the draw at the All England Club. He defeated Richard Gasquet in the semis. In the finals, Roger met—who else?— Nadal. Their match lasted five grueling sets, with Roger winning two tiebreakers before taking the finale with relative ease, 6–2. The last time anyone had stretched Roger to the limit at Wimbledon was in 2001.

Roger won his 50th career singles championship in Cincinnati later that summer. Next, he captured the U.S. Open again, beating Novak Djokovic in the final. Roger finished another #1 season by beating Nadal in the Masters Cup semis on the way to the championship.

Roger started 2008 as the prohibitive favorite in Australia, but was bumped out in the semis by Djokovic, who went on to win it all. It was later revealed that Roger had been the victim of food poisoning. Later he announced that he had been diagnosed with mononeucleosis. Predictably, he showed poorly in the other early season tournaments.

Roger soon hired a new coach, Jose Higueras. In his first appearance under his tutelage, he won the Estoril Open in Portugal. His opponent in the final, Nikolay Davydenko, retired after suffering a leg injury in the second set. The previous year, Davydenko had pulled out of a match with a foot injury, triggering an investigation by the ATP. More than a million dollars had been bet against him by Russian gamblers in that match. Davydenko was ultimtely cleared of the charges.

Roger faced Nadal in the finals of two clay court tournaments that spring and lost both times. They also met in the finals of the French Open, where Nadal destroyed him. Roger lost one of the sets 6–0. The last time he had been bageled was in 1999.

Roger tightened things up in the weeks before Wimbledon and was sharp throughout the tournament. The tennis world watched in delight as he and Nadal headed for a second straight clash in the final. Roger had a chance to break the modern record with a sixth consecutive championship.

The match went on all day—almost literally. Thanks to rain delays, it lasted over seven hours, with nearly five hours of breathtaking tennis. Nadal seemed to have the upper hand early on, taking the first two sets 6–4, 6–4. But Roger fought back in the third, winning in a tiebreaker. He took the fourth set in a tiebreaker too, saving two match points in the process. The fifth set featured one spine-tingling point after another. Nadal finally prevailed 9–7. Most people who watched the two superstars battle said it was the greatest match they’d ever seen.

A month later, Nadal surpassed Roger as the #1 player in the world. Roger had held that honor for a remarkable 237 consecutive weeks, easily eclipsing the men’s record (160, by Jimmy Connors) and women’s record (186, by Steffi Graf).

After winning a gold medal in doubles at the Olympics, Roger put his stamp on the U.S. Open for the fifth year in a row. After survivng a tough match with Igor Andreev in the round of 16, he beat Gilles Muller, Djokovic and Andy Murray for the championship. Murray had stunned Nadal, denying fans in Flushing Meadows a chance to watch a 7th Federer-Nadal Grand Slam final.

Those who claim Roger belongs in the same class with players like Bill Tilden, Rod Laver and Pete Sampras no longer have to defend their view. When Roger is playing his best, he is as good as anyone who has ever taken the court. He can do more to beat an opponent than anyone on the tour and isn’t afraid to adjust his approach if the situation warrants—or if he just feels like it. In an era when rackets amount to little more than power tools, Roger hand-crafts his wins. That type of virtuosity was thought to be a thing of the past not too long ago. Hopefully, for Roger and the rest of tennis, it’s a sign of the future.

ROGER THE PLAYER

Though capable of overwhelming most of his opponents, Roger prefers to pick their games apart—sometimes exposing their weaknesses, sometimes finding ways to use their own strengths against them. These cat-and-mouse games used to be his undoing, but he has perfected his craft, and now it his opponents who look helpless at times, not him.

Roger’s anticipation and footwork are as good an anyone’s on the pro tour—and maybe ever. His volleying skills are matchless among current ATP players, and the best the tour has seen since John McEnroe’s. Surrounded by super athletes who wield ultrapowerful rackets, Roger has reintroduced the slice to men’s tennis. So few current players have experience with this “weapon” that it has become one of Roger’s most effective approach shots.

Despite his reputation for finesse, Roger does not lack a power game. His strokes are so effortless, it seems impossible that he could generate the pace he does, but clean winners don’t lie—he hits as many as any top player. The same is true of Roger’s serve, which is well above average.

Off the court, Roger’s courteousness and openness have endeared him to the tennis fans. There may not be a nicer guy on the tour.

Those who believe Roger is as good at this age as anyone in history point to the fact that, unlike Laver and Borg, he is comfortable on hard surfaces, and can dominate on them. And unlike Sampras and McEnroe, his game is championship-caliber on clay.

Peter Carter and Roger Federer

CLICK HERE to watch the Virtual Tennis Coach tribute to Peter Carter

‘The Development Stage’ DVD Dedication:

“This DVD is dedicated to two young men with whom I’ve enjoyed an enduring friendship. To Lleyton Hewitt, the best pupil and the best player that I have had the good fortune to be involved with, To Peter Carter, who was like a son to us and whose achievements in coaching, with Roger Federer, the Swiss Tennis Federation and the Swiss Davis Cup Team, I’m in awe of.”

Peter Smith